This past spring, artist/researcher Amy Suo Wu spent three months in Beijing developing "The New Nushu." We had the opportunity to interview Amy about the project, her experience in Beijing and the residency at I: project space.

China Residencies: How did you first hear about the i: project space residency?

Amy Wu: Through China Residencies, back in 2015.

CR: Tell us a little bit about your background and practice as an artist.

AW: I have a hybrid practice as graphic designer, artist, media researcher and educator. My cultural background is Chinese and Australian, but I’ve been living in Rotterdam for the last 11 years. After finishing my Masters in Media Design at the Piet Zwart Institute, I co-founded Eyesberg, a commissioned-based graphic design studio. In the same year I also started teaching at the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam working in the graphic design department and a minor course called 'Hacking' to students across all disciplines. My practice harnesses and combines aspects of these fields.

For the last few years I’ve been exploring the art, science and politics of steganography, a form of secret writing that hides private information in the public eye. Unlike cryptography, which provides privacy by scrambling messages through the use of codes and ciphers, steganography is intended to provide secrecy by hiding messages in plain sight. Some techniques include invisible inks, Cardan Grille and text camouflage. ‘Tactics and Poetics of Invisibility’ is the title for the body of work that experiments and researches low-tech, analog and obsolete steganographic tactics to protect the communication of citizens and communities, as a response to the rising issue of high-tech governmental and corporate spying online. Within a Western context, my focus was on alternative interpersonal communication channels against pervasive surveillance. However, within the context of Beijing, my focus shifted to exploring steganography as an alternative publishing channel to evade pervasive censorship.

CR: How did the idea come about for the project you created at i:project space?

AW: Thunderclap is the first manifestation of a research framework called ‘The New Nüshu,' developed during my residency to better understand the relationship between censorship, publishing, steganography, language politics and Chinese feminism. One can see ‘The New Nüshu’ as the mother of Thunderclap.

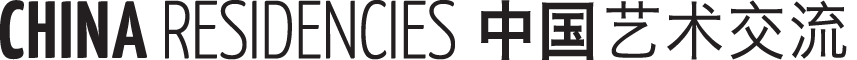

Thunderclap is the project that uses fashion to spread the writing of He-Yin Zhen. Photographer: Jeff Yiu. Models: Zhuxin Wang, Tu Lang, Amelie Kahn-Ackermann

The original Nüshu (“Woman’s Writing” in Chinese) is an endangered secret script created and used exclusively by women from Hunan province, reaching peak usage during the latter part of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). Nüshu allowed these women to keep autobiographies, write poetry and stories, and communicate with “sworn sisters,” women who were not biologically related. It served to create social cohesion as they could better express their feelings in a male dominated society. It is also possible that during the Japanese invasion in the 1930’s-1940’s, the script was suppressed because they feared the Chinese could use it to send secret messages. However the native use of Nüshu was never meant to be a secret, in the sense that it wasn’t designed to exclude men – rather men knew very little about it or weren't interested. In this context, ‘code’ or ‘secret’ refers to the unknown and less about the deliberate withholding of information. Women developed an alternative system not to dismantle the systems of oppressions but rather to cope with it, by giving themselves a tool to help express their emotional turmoil.

From the standpoint of my artistic research on steganography, I was drawn to Nüshu’s potential as a code to evade surveillance and to form community; however, it quickly became clear that issues of gender and Chinese feminism needed to be addressed in combination with the former two threads. This is the premise under which “The New Nüshu” project was born. Inspired by the original Nüshu, I started to think about what the new Nüshu would look like if it existed today. I wanted to initiate a project to collectively develop a new contemporary female writing system entailing discussion, research, design and exploration of the political/social/cultural potential of such a code. This became the pretext for me to invite other women to come together to share stories, experiences and thoughts on what it’s like to be a female living in China today.

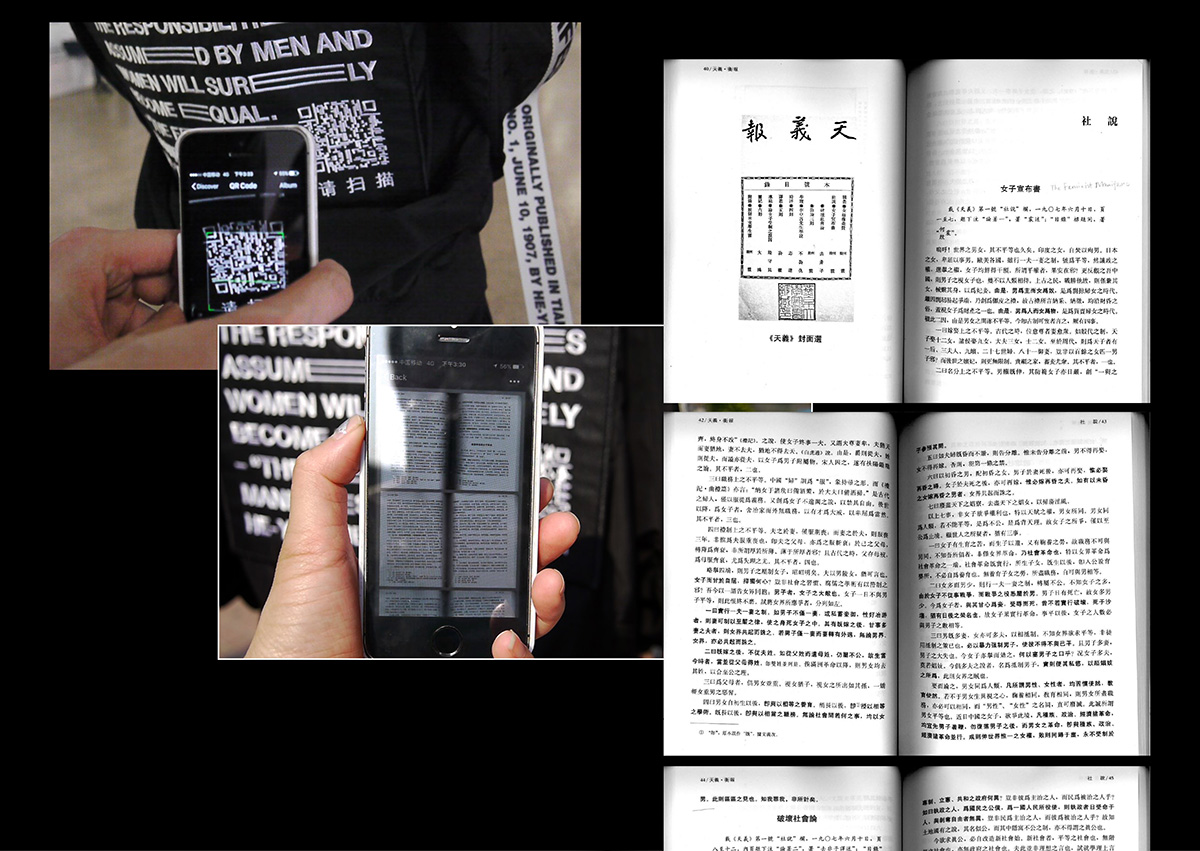

Due to time limitations, I realised that this project required more time to develop and so I settled on producing a smaller work. During my time there, I was fortunate enough to meet and hang out with the Q-space (queer/feminist/maker space) community. On my first visit one of the members introduced me to their library and the book “The Birth of Chinese Feminism: Essential Texts in Transnational Theory.” Through this book I became aware of the thoughts and writings of He-Yin Zhen (1886-1920) — an early anarcho-feminist and female theorist who figured centrally in the birth of Chinese feminism. Together with other Chinese revolutionaries in exile in Japan, He Yin Zhen co-founded and edited one of the first Chinese language anarcho-feminist journals called “Tianyi Bao” or “Natural Justice”. Even though it was highly influential in the spreading of radical ideas such as feminism, socialism, Marxism and anarchism in the last decade of the Qing dynasty, He-Yin Zhen’s is still a relatively unknown figure in China and abroad. Furthermore, it was this journal that first translated “The Communist Manisfesto” from Russian to Chinese in 1908. The significance of this detail has been overlooked: it was the feminists who had first translated communist thought and other radical ideas into China.

I began asking people around me for more information about this incredible women. I soon realised that nobody knew who she was. Book shops I visited didn’t stock her work, and there is very little information online. Many questions arose: Why has she been forgotten? Has she been erased deliberately? What happened to her legacy? In the book “The Birth of Chinese Feminism” the authors suggest that her writings were gradually erased from the historical record in China because it was considered too radical and dangerous in her lifetime.

A few people also asked me if her original writings in Chinese were available for a Chinese audience. This set in motion the goal of the project, which was to make her work more accessible in hopes of reinserting her back in Chinese history and public knowledge. However I felt that it was also important to compromise accessibility/visibility as a tactic to protect content that would otherwise remain silenced if they were in legible and visible form. Thus the technique of steganography found its way back into the project, via instrumentalising fashion accessories as a guerrilla publishing medium. These accessories were patches and ribbons on clothing, which contain quotes from He-Yin Zhen’s essay in English nested around a QR code that when scanned, downloads her original Chinese writing.

CR: How did steganography and fashion come together in your mind?

AW: As it has always been a closeted interest of mine, one of the very things I first noticed in China was street fashion. I actually wanted to study fashion or fine arts after high school; however my father disapproved, so we settled on design. Like many things in China, street fashion is wildly fresh compared to Europe. The West has constructed notions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘originality’, which has shaped the discourse around ownership/property amongst other things. The global rhetoric is the Chinese ‘inauthentic’ remixing of ‘authentic’ Western culture. The culture of shanzhai challenges that fetishisation and allows for ‘counterfeits’ to flourish; pirated movies, fake brands, imitation European cities, fake electronics, and copied designer fashion etc. (For more on the subject of shanzhai, this book will be published in English at the end of this year: Deconstruction in Chinese by Byung Chul Han)

The current Chinese fashion trend is to use English black and white text on clothes as a value signifier, appropriated from Western fashion labels such as Moschino, Hood by Air, and Supreme (for more of an impression, check out T-shirts of Beijing Instagram account). The aesthetics of Western culture is signified through latin based alphabet and literally becomes the embodiment of ‘high culture’. As a result, English text here functions as a decorative ornamental rather than to literally read: but for english readers, texts often appear like dada poetry, non-sensical wisdom or hilarious word salad. Everyday I really looked forward to these moments of poetry when I could read the backs of people’s clothes while waiting at a bus stop, subway platform, escalator, or red-light crossing.

Photographer: Jeff Yiu. Models: Zhuxin Wang, Tu Lang, Amelie Kahn-Ackermann

After some time I started to see them as walking billboards, potential alternative and self-publishing platform to explore. Moreover I saw the advantage of using the fashion trend of decorative-English-text as a steganographic element to covertly publish and distribute sensitive, forgotten or erased content precisely because it is overlooked, deemed innocuous and politically harmless. I also wanted to hint to the process of reclaiming shanzhai culture to be understood through it’s own frame and not in the shadow of the West’s monopoly over what constitutes as ‘value’.

In my research of secret messages I came across many historical examples that could be seen as ‘subversive decoration’, such as this historical cross stitch made by a British POW in a Nazi prison camp during WWII. His captors never found out, but the decorative pattern in the frame is in fact a secret message in morse code, spelling out ‘God Save the King and Fuck Hitler”. This idea of using what is at hand to subvert or cope has always been personally close to me. Fashion can be decorative but also instrumentalised for identity politics. I wanted to push the medium of fashion as a political and publishing medium beyond the catwalk/art gallery and onto the street.

CR: What drew you to He-Yin Zhen’s writing?

AW: In general I was impressed by her thorough analysis and perspective on the relationship between class, gender and wealth inequality. One of her main points is that the emancipation of women should not only improve the most privileged women, but all women – and by extension the opression of women can’t be properly eliminated until poverty and private property are also abolished. Her writings remind us that feminism is not only a contemporary (Western) consciousness but also one that was articulated in imperial China. Furthermore, according to the authors of the book, no other feminist in the world, at the time wrote such radical critique both in depth and breadth.

However, there was one point that especially resonated with me. I was particularly amazed by her sharp – and in my honest opinion, still contemporary – critique towards how the feminist consciousness was (ab)used for ‘civilising’ causes in both China and the West. In China’s case, it was instrumentalised for the sake of modernising the nation and in the West to upkeep a 'progressive' superiority.

I would also like to add that this is the first project in which I've explicitly addressed the feminist struggle. I guess one of the reasons why I actively engaged with this conversation in a Chinese context was because the construction of gender norms and attitudes that my parents transmitted to me came from their Chinese cultural heritage. Somehow these stereotypes weighed heavier on me and I was provoked to challenge them. In any case, I see this project as the thematic sedimentation of many other projects, e.g steganography, surveillance but also my interest in finding and learning about underground, lost, erased knowledge that undermine official historical narratives, which ultimately questions discourse regimes and how they shape reality through the management and construction of acceptable knowledge.

CR: Does it matter whether people can read and understand the English on the clothing?

AW: Even though I designed this for a Chinese audience in China, I deliberately chose to use English on the patches and ribbons as subversive decoration around the QR code and its caption underneath in Chinese text saying “scan to download text”, which is in fact the actual the centre of this piece. Much like the “Fuck Hitler” cross-stitch example, I’ve used English as a ornamental feature to ‘smuggle’ in the QR code. However my I:projectspace assistants and friends, Zhuxin Wang, Yiyi You, and myself spent a lot of time choosing the right quote in case of English-readers. After hours of consideration I decided to choose the general and timeless quotes over the radical and provocative ones, for the reason that I didn’t want to cause potential harm to the person who wore my patches in case they didn’t understand the English text.

CR: Why was it important to work with QR codes in this project?

AW: In the same vein as instrumentalising popular fashion to allow for further distribution and circulation, the QR code was used for its ubiquity in China – that it has become a ‘habitualised’ mode of information access and as a result its pervasive visual presence inadvertently provides an inconspicuous cover.

CR: The QR codes conceal hidden messages, taking those who scan between the English to the original essays written by He-Yin Zhen. How did you develop this steganographic practice of “instrumentalizing art to circumvent surveillance”?

AW: My interest in the steganography in relation to the politics of visibility began 2 years ago with my project ‘Tactics and Poetics of Invisibility’ which aimed to investigate ways to evade high-tech surveillance with lo-tech protection methods. You can hear more about the project in this talk. Over the years, I’ve produced a body of work that resuscitates and repurposes forgotten steganographic techniques for contemporary surveilled mediascapes. So even though many of my works attempt to instrumentalize art in order to circumvent surveillance, I feel that my recent solo show at Aksioma called “The Kandinsky Collective” is able to propose how this may function on a larger scale. The show uses speculative fiction as a strategy to shed light on the discourse of privacy, surveillance and the instrumentalisation of art and graphic design in media activism. Departing from the rumour that during WWII the artist Wassily Kandinksy was recruited by the British Intelligence to smuggle secret communication by encoding it into his abstract, systematic and symbolic artworks, The Kandinsky Collective exhibition explores the subversive potential of using the formal language of contemporary 'high' art as a means to embed hidden messages. Set in the near future when privacy has become a crime, the exhibition is in fact a staged exhibition of privacy activists posing as a contemporary art collective, where they co-opt abstract art as a cover to form an underground communication channel.

My interest in steganography was inspired by an article about the CIA declassifying WWI invisible ink recipes. Invisible ink is in fact, one of the oldest forms of steganography, dating back to the third century BC. Despite the military incentives, I was impressed by the inventiveness, and creativity mentioned in the article. The recipes describes how to carry invisible ink in your clothes. Spies were instructed to soak their handkerchief or collar in invisible ink so they wouldn’t get caught with it. According to the article from 2011, the CIA had only released the documents because these old techniques are now considered harmless – no longer posing a threat to national security since advanced digital technology has rendered them obsolete and useless. Triggered by a comment in one of the articles, I too questioned whether such old techniques were as innocuous as they were considered. If people were to communicate safely, it would be via analog means because paper can’t be tracked in the same way. This was the conception and premise of my steganographic practice.

CR: How did people react to your project in public in Beijing?

AW: As far as I know, quite positive. Many Beijing women expressed interest in being involved with “The New Nushu” project in the future, which I was incredibly humbled by. However the process and development of the project itself also inspired a lot of engagement which was just as important for me.

There is one person’s reaction I would really like to know. This particular person was an anonymous man who kept on showing up at a few of my events who we suspected was a government official.

CR: Do you know how many people have downloaded the original Chinese text?

AW: I don’t know.

It could be interesting and insightful information for the development of the project to keep track of download data such as the frequency and location, especially in light of the goal of spreading He Yin Zhen's text. However i'm conflicted by the tracking possibilities. In one way, I will be put in a position in which i’m doing the surveillance and monitoring...however the broader reality is that by placing the essays online, data collection is possible by any 'interested' third party. In this sense, the online aspect of this work is a double edged sword. On one edge, it allows her work to spread across national boarders that may contribute to the transnational discourse on uneven hierarchies between gender, class and labour. On the other side, it is vulnerable to those who want to incriminate the downloaders.

Having said that, there are some ways to momentarily maneuver around it. VPN's are used to access Western platforms outside of China such as Whatsapp or Facebook to communicate, not because it's less surveilled –Snowden can verify me – but because it takes longer for the Chinese state to retrieve data instantly, which they can do with Wechat.

CR: For the final event of your residency, you turned your studio into a DIY space for people to customize their clothing with ribbons and patches. Who came to your workshops, and what do you think they came away with?

AW: The DIY event was super emotional and rewarding for me. It was my final event and I was to return home the next day. A lot of people from the arts and cultural scene were squeezed into my tiny space equipped with scissors, pins, needles and thread in their hands. For me it’s fulfilling to see people involved in the process of a work that becomes their work too.

It was also great to see the neighbors from the hutong come in and hang around. One of my regrets is not communicating enough with them since my Mandarin was limited. Next time I really want to improve my Mandarin to have more conversations with locals.

Final event for Thunderclap, a DIY open studio

CR: Can you talk more about the use of quilts/blankets in your project?

AW: In hutongs, Beijingers hang up their blankets on the street with makeshift clothing lines tied to whatever structure lends support i.e. lamp posts, trees, electricity posts and air conditioning cages. I enjoyed seeing how people made use of their immediate surrounding as an extension of their home, blurring the boundaries of public and private space.

Seeing them everyday reminded me of the ‘slave quilt code’, a code stitched onto quilts that African American slaves used to navigate the Underground Railroad. Quilts with patterns named “wagon wheel,” “tumbling blocks,” and “bear’s paw” contained secret messages that helped direct the enslaved to freedom. Although it’s existence and credibility is contested, it inspired me to think about the potential of reenacting this tactic as a covert publishing platform in the context of the hutongs.

Another example that relates is one that Professor Zhao spoke of during our meeting. Professor Zhao is head of the Nüshu preservation research team at Tsinghua University, and together with I:projectspace assistant, Zhuxin Wang, we had the fortune to spend an afternoon with her and her associates. She mentioned that in the same province where Nüshu was developed, although from a different minority group, women used a secret symbol system to reach out to their own family when in need of protection from the family in-law as wives were often treated as servants to the husband’s household. Unfortunately I do not have any visual references, since further research into this phenomena still needs to be done.

Within the hutongs, blankets can be seen as a transgressional object migrating between the public and private sphere. They’re also a mundane household item that moves inside and outside of the confines of the house without raising any alarm bells. In this way, the blanket is a perfect cover, literally speaking but also as an unsuspecting agent that can smuggle and ‘air out’ private information into the public. In fact, in the English language, laundry metaphors already point to this direction. To ‘launder’ is used to refer to the act of legitimising illegally obtained money – to wash away it’s questionable traces. In contrast, to ‘air out dirty laundry’ is analogous with disclosing private secrets publicly. The first speaks about erasure, hiding, removal, suppression, censorship and the latter refers to revealing, talking, making public, leaking, publishing. Furthermore, the fact that they are a common sight means that the content embedded into the blankets is hidden in plain sight, an act of steganography that not only evades surveillance and censorship but also protects the identity of those who might be involved in the project.

Quilts are also often the result of women’s labour, a symbol of domesticity and of community. By using this surface, we attempt to reclaim that space.

I made a first attempt to publish content from the ‘Thunderclap’ project on the medium of the hanging blanket. My intention is to develop this idea further for The New Nushu project when I return to China.

Quilts as steganographic practice in Beijing

CR: Tell us a bit about your time in Beijing.

AW: My trip to Beijing was incredible, even life changing, I believe. So much to see, so much to do, so many people to meet….all the time. I spent lots of time hanging out with my I:projectspace family Anna and Antonie and co-resident Juliet Carpenter.

Thinking back, I was really happy there. Our residency was in an old hutong, and so there was a sense of neighborhood with the local residents and shop owners. Since our space didn’t explicitly look like an art space, I often had to explain to our curious locals what the hell we were doing in there. Some thought we were a school, given that I had my research on the history of the Chinese language stuck on the wall, others thought it was a copy shop given that we had a printer, a tailor shop given that I had a sewing machine on my desk and a massage parlour, of which I never figured out the reason.

I really enjoyed being surrounded by Mandarin, listening, speaking and learning it. Another feeling which was totally new for me was being invisible. It was such a relief to not be afraid that some ugly racial comment would get spewed at me on the street. No one looked at me strangely, I was camouflaged…until I opened my mouth and my broken Chinese blew my cover!

CR: What were some of the challenges while in residency? What was easier or more difficult than you expected?

AW: I had been mentally preparing and waiting for this experience since 2015. I was a little cautious since it was my first ever artist-in-residence so I really didn’t know what to expect in terms of the residency. However when I arrived, Anna and Antonie (the I:projectspace founders) were the most supportive and warm people to have as hosts.

The most difficult thing was catching up with my ambition! So much stimulation and ideas pouring out that I couldn’t find enough time to digest them, let alone find form for them.

CR: What have you been up to since the end of the residency? You note that Thunderclap is part of a larger body of work, The New Nushu. What’s next for the project?

AW: After Beijing I went into another residency at ZK/U in Berlin, which was directly influenced by my project and experiences from China. In Berlin I spent the time re-thinking and reevaluating the conversation we have in the West on digital surveillance from a feminist and post-colonial point of view. Shifting the perspective of general surveillance studies that addresses white men as the neutral population (given the tech community is predominately white and male), I was thinking about the colonial legacies of surveillance and how this continues to affect marginalised groups. The project I developed from this line of thought is called “Shanzhai Passport”, a counterfeit passport stand offering forged passport services. Attempting to put into action the articulation of Iranian design researcher, Mahmoud Keshavarz, that passport forgery can be viewed as a ‘critical practice of making which momentarily interrupts the matching accord of body, citizenship and freedom of movement’, these fake passports not only tries to place questions of race and empire at the centre of the surveillance discourse, but also how this continues to perpetuate the construction of illegalised bodies from the ’third world’ and illegal counterfeit products made in Asia.

In terms of “The New Nushu”, my intention is to come back in 2018 or 2019 to continue the project. In the meantime I’ve documented the project here in the form of a website, which I intend to print as a book for people who might be interested in participating.

CR: How were the residency at I:projectspace and being in Beijing helpful in facilitating collaboration?

AW: Anna and Antonie were very helpful in facilitating meetings with people, they are very well connected and supportive in general. They brought me in contact with the Q-space community and many strong and admirable female characters. They were also very engaged in the process and research development of my project.

CR: Had you spent time in China before the residency?

AW: Since immigrating to Australia in 1991, I’ve returned every few years to visit family and my place of birth in a small city called Shantou, situated in the province of Guangdong, where they speak the Teochew ‘dialect’.

Because we maintained contact my interest in China grew. However when I realised that most of my impressions and understanding of China was filtered through their lens, I desperately wanted to see more sides of the China-universe through my own eyes. I felt like I owed it to my myself to see the complexity in all it's beauty and ugliness.

CR: What was your experience like, as someone from the Chinese diaspora, to go or return to create this project?

AW: To be honest, I’m still in the midst of making sense of my time there. For me, it was something that was so much more than just an art residency, it was a journey to this (un)home that kept a piece of me. I feel that for the very first time in my life, I was able to retrieve this piece of me again. When I returned to Europe with this new piece, I was suddenly able to see my life before I had retrieved this piece in a different light and this shook me to my core. Right now, I am in the aftermath of this quake – I swing from being super excited and shit scared to rebuild again.

Since I’ve been back in Europe, I feel like i’ve come out of the closet as a ‘Chinese diaspora’. I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about what it means to grow up in the West with the constant feeling of displacement but also the struggle of coping with everyday racism. I can feel that this journey has already started to reshape my identity, politics and practice, only i'm not quite sure where it will take me yet....

CR: How do you imagine Thunderclap and the New Nushu continuing in Australia and beyond?

AW: There are some things lined up in the near future. I’ve been invited to a guerrilla communication festival called The Influencers in Barcelona next month to talk about my experiences in China, Thunderclap and The New Nushu project. I was also planning to host a few more Thunderclap DIY customisation events locally in Rotterdam. As for the rest, if anyone is interested in hosting one in their locality, they are more than welcome to get in touch with me. Also get in touch with me if you have any suggestions or if you are interested in buying the patches or ribbons. Here is the project link.

And as for the distant future, I hope this project can continue to facilitate needed moments of collaboration, dialogue, understanding and learning.